Highlights of the British Collection: East Oxford Archaeology

Object Biographies - A Stone Head from St. Clement's, Oxford

by Nina Curtis

Contents

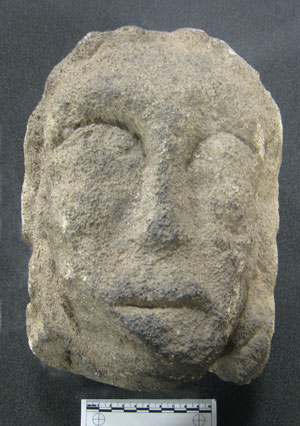

In 1912, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford purchased a stone carving of a head. The Museum's record (AN1912.2) describes it as:

Large stone head; ? Headington stone face mutilated; in cowl or wimple; H. 332mm, W. 175mm; Depth 158mm; part of architectural detail. Source St Cement's Oxford. Purchased. From site of old Almshouses, demolished. (In 1912 this would have been the site of Mission Hall, 56 St Clement's) [1] [2]

Stone Head, front view (AN1912.2)

Dr. Jim Harris, Teaching Curator in Western Art at the Ashmolean and a scholar of Renaissance polychrome sculpture, was kind enough to give his opinion. He felt it was definitely the likeness of a male individual, probably 13th century, and probably carved from Headington stone, and also that it almost certainly originated as a corbel,[3] with supporting stone arches springing up from the top of its head to the roof or arcade of a church, chapel or similar religious building, and that it would have originally been painted.

Marcus Cooper, professional stone mason and archaeologist, was also kind enough to examine the head. He agreed that it seemed to represent a male, and he also observed that the level of sophistication in the carving was not high and thought it might well have been part of a corbel table, sited high up in a church. [4]

Because the head is both weathered and mutilated, it is difficult to envisage what it would have looked like when it was created. The lower right-hand side of the face/chin has been cut off, and the finer details of eyes, nose, hair and mouth have blurred with the passage of time, but we can still discern the main features:

- it appears to be a male likeness

- it has fairly high cheekbones

- the lips seem to be full rather than narrow

- there is no head covering

- shoulder length plaited hair is visible on the left hand side of the head

- a tight collar or neck covering is worn, similar to that of a wimple (but wimples were exclusively worn by women – especially nuns). Could this possibly be female and, if so, who or what is it meant to portray?

- the back of the head is flat, where it was attached to wall

- the top of the head is relatively flat, but there are two faint grooves in it, perhaps indicating where it joined the underside of a corbel table, stone arches or other structures that sprang upwards

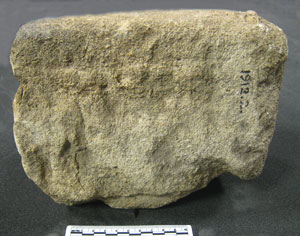

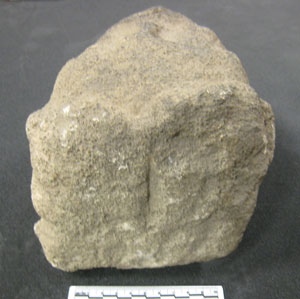

Stone Head, right side (AN1912.2)

Stone Head, left side (AN1912.2)

Stone Head, back (AN1912.2)

Stone Head, top (AN1912.2)

It soon became clear that the Almshouses referred to in the Ashmolean's accession record were the Cutler Boulter Almshouses, and that the head could not have originated there, as those Almshouses weren't built until 1736 and were therefore far too recent to have housed the head in their chapel. There are no specific records of any buildings that pre-existed the almshouses on this site, and what buildings there might have been were almost certainly domestic, so we do not know how the head found its temporary home at 56 St. Clements.

After residing in the archives of the Ashmolean for 102 years, and almost 800 years after it was created, perhaps the time had come for its story to be told. It therefore seemed best to go back to the beginning and trace the genesis of this head and the geological processes and human interventions that created it, and then try to ascertain where it came from, who might have sculpted it, and what significance it might have had for the people who viewed it.

The stone used to produce the head almost certainly came from a quarry in or near Oxford, and the quarries in Headington and Wheatley are the most obvious candidates because of their close proximity to Oxford. Approximately 150 million years ago, in the Later Jurassic period, much of the eastern side of Oxford was a shallow tropical sea (similar to the Bahamas today), with ribbons of coral reef running through it. These coral reefs were eventually fossilized and transformed into a very hard limestone known as Coral Rag. This stone, which was incredibly durable and almost impervious to weather, was used extensively in Oxford and other prestigious sites.[5]

The channels of water that ran through and intersected the coral reefs produced two further types of stone: Headington Hardstone and Headington Freestone. The oyster shells and oolites that made up a good part of the composition of these types of stone was not as hard as Coral Rag, but the Hardstone was still considered to be extremely durable.

The Freestone (so called because it was soft enough to be freely carved in any direction with a saw), was not as durable but more easily worked, and so it was used extensively in stone dressings.[6]

A particular quality of Freestone is the way in which it weathers, particularly in the presence of air pollution: a hard skin forms on the surface of the stone; blistering of the skin occurs, the blister crumbles and results in exfoliation of the outer skin, and then the whole cycle begins again.

Although the stone used to make the head has weathered, it has not weathered in the manner that Freestone degrades, and is more likely to have been made from Headington Hardstone (although no tests have been performed to prove that this is the case). Marcus Cooper observed that the stone was of a hard consistency (for example harder than the Bath Stone that he often works with), and he also felt that it was likely to be Headington Hardstone, rather than Headington Freestone. [7]

Headington stone first appears in Oxford records in 1396-97, when Headington Hardstone was purchased to build New College bell tower [8], but it was almost certainly in use well before that, as there is evidence of much earlier working of the quarries. The economy of Oxford was greatly boosted by the local stone industry: almost every Oxford college was built from local stone, and it was also in demand elsewhere (Eton College and Windsor Castle were constructed mainly from stone quarried in Oxford). Not surprisingly, there arose an extensive and intricate network of builders, carpenters, and especially stone masons, in and around Oxford to support and serve this thriving trade.

4. The First Home - St Clement's Church?

We will probably never know where the head was originally sited. It almost certainly comes from a religious environment, but it is doubtful that it came from one of the grander Oxford churches or college chapels. While it is not crude, neither does it appear to be a highly sophisticated carving and, when compared to some of the masterpieces in other religious and academic buildings in Oxford, it seems likely that it was carved by a mason, but perhaps someone with less stature than the master masons or master carvers who worked on the colleges and prestigious churches in Oxford. Also, our nominal date of the 13th century excludes many of the colleges which were built later. In the Middle Ages, and not far from where the head was said to have been discovered, there stood the small parish church of St. Clement's, which served a poor community that could not have afforded the services of a master mason, and this could well have been the original home of the head![]() [9]

[9]

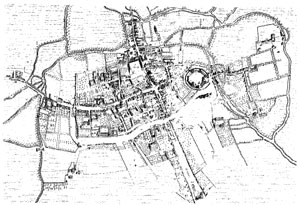

The parish of St. Clement's lay outside Oxford's East Gate and just the other side of the bridge that crossed the river Cherwell. Indeed, the area and its manor were originally called Bruggeset (derived from the Old English brycg (bridge) and (ge-)set, (dwelling). The manor of St. Clement's was granted to St. Frideswide’s monastery in 1004, and the royal chapel of St Clement's was given to the Priory by Henry I in 1122. Oseney Abbey and the Abbott of Eynsham also staked claims to land in St. Clement's, and there was some tension between the houses, which was eventually resolved in favour of St. Frideswides.[10] There was never a vicarage in St. Clement's, and the church was presided over by various chaplains and rectors.[11]

St. Clement's Church stood on what is now called The Plain, from sometime before the 12th century until 1828, when it was demolished and a new church built in Hacklingcroft meadow further north and east of the old site. The community of the church had always been small: in the late 13th century 28 cottages were owned by St. Frideswide's, 18 houses by Oseney Abbey, and 5 houses by St. Bartholomew's Hospital.[12] In the early part of the 19th century, however, there was an influx of young academics (in 1800 the parish still consisted of only 400 people, but by 1824 the population had increased to 2,000),[13] and this meant that the church was no longer large enough nor, because of its position, could it be significantly extended. The three bells from the old church (one dating from the 13th century and thought to be the oldest bell in Oxford) were taken to the new church. Could the head have been removed from the church at this late date?

There is little evidence as to what the original church looked like, but the Victoria County History states that

'In 1323 there was an indulgence for the fabric of the church of St. Clement beyond Petty Pont [the old name of Magdalen Bridge], and it is probable that most of the building destroyed in 1829 dates from this time; some of the stonework demolished was, however, thought to belong to an older 12th century church.'[14]

Could the head have belonged to the original church and been discarded when it was refurbished in 1323? If so, where did it reside for the next 600 years, until it was bought by the Ashmolean?

There are no drawings or detailed plans of the original church, but Sir John Peshall in 1773 says:

'This church is composed of one isle thirteen yards long (exclusive of a chancel six) and six yards and twenty inches broad. On the north-east and west sides are galleries. Over the latter is a small capp'd tiled tower containing three bells.' This bellcote was replaced in 1816 by a square tower built of lath and plaster at a cost of £80.'[15]

It is interesting to note that cowboy builders are not a phenomenon of the 21st century, as records show that only six years after its completion the tower was reported to be in urgent need of repair![16]

The medieval church of St. Clement and the small community that surrounded it were positioned on an important entrance to the city: it was the place where roads from the east converged to cross what is now Magdalen Bridge and proceed into the city. In addition to being the primary route from London into Oxford, these roads also carried timber from the forests of Shotover and stone from the quarries of Headington and Wheatley into Oxford. So important was this road, that from time to time, in addition to grants from the City, contributions were made from such luminaries as Richard II and Cardinal Wolsey towards repairs to the roads. Parishioners, however, were not exempt from the costs of keeping the roads in good condition, and they were frequently prosecuted for failing to provide carts, stones, and labour for repair of the roads.[17]The burden of road repair exacerbated the extreme poverty and consequent suffering of the people of this small community, and it is unlikely that they would have been able to afford the services of a master mason to work on their church.

Map of Oxford by Wenceslas Hollar, 1643. North is at the bottom of the map, and St. Clement's and its church can be seen on the left, just to the east of the river and bridge.

Painting of St. Clement's Church by William Calcott, 1778, showing old bellcote. (Available on the British Library Online Gallery)

Postcard of St. Clement's Church from the South, howing square tower that replaced the old bellcote. (Available online)

St. Clement's Church from the Northwest, showing toll house at western end (old postcard) (Oxfordhistory.org website)

We do not know when the church of St. Clement was first constructed, but it is possible that at some point in the 13th century our head was added to the structure. The parishioners of this impoverished community could not have afforded to employ the best craftsmen – the men who were building and decorating the colleges of Oxford ¬ but they would have hired a variety of qualified builders, carpenters and stone masons to work on their house of God.

The life of a stone mason in 13th-century Oxford was rigorously prescribed, with varying recognised levels of skill and responsibility, and the best masons combined the roles of designer, architect, craftsman, builder and engineer. Some of the listed classes of stone mason were: master mason, servant to master mason, mason, servant to mason, master stone carver, stone carver, warden of masons, rough mason, paviour, mason's labourer, freemason. Each of these trades had particular skills and duties, and if their duties were not fulfilled they could be prosecuted in court. The most important mason was the master, who made the design and controlled the work, subject to the wishes of his employer.[18]

Although some masons travelled long distances to work on the massive building sites of the colleges in Oxford, most of the masons were local, and it is likely that the man who carved the head was a local craftsman who had previously been apprenticed to a master carver or master mason and was now working for himself. Many of the masons undertook one-off jobs in addition to their college work, and they were often given lodging for the duration of their employment, both for themselves and their families.[19]

The head is not a particularly sophisticated carving and, when compared to some of the masterpieces in other religious and academic buildings in Oxford, it would appear to have been perhaps carved by someone with less skill and status than a master mason or a master carver. By looking more closely at the life of a typical stone mason in Oxford during this period, we can get some feeling for the life of the man who might have sculpted the head.

Richard Norton was a mason who worked in Oxford towards the end of the 14th century, and although the head was probably carved earlier, it could have been someone similar to Richard who produced the head. He would quite likely have had no formal education, but would have served an apprenticeship to a highly qualified mason, during which time he would have learned his trade and also acted as 'beer boy' during breaks and meal times.[20]

At the end of his apprenticeship Richard might well have travelled in search of work and been paid on a daily basis. Pay varied by season, as well as relating to the job. It is recorded that the average mason who worked on the building of All Souls in 1437 was paid 6d. per day in the summer, but in November this was reduced to 5d,[21]most probably because at that time of year working hours were fewer due to reduced hours of daylight and inclement weather.

It is known that Richard lived outside the North Gate of Oxford with his wife, Alice. He was one of many masons who worked on the New College building site, and when the College was finished he was privileged to attend the Great Gaudies that were held there in celebration on completion of the building work. In 1391, he served as a constable, 'whose duty it was to return the names of men accused by twelve jurors, under the Statute of Labourers, in the Hundred and Suburb outside the N. gate. He was himself one of the offenders on this occasion and was fined again in 1392 and 1394, but was also at one time one of the jurors'.[22] [23]

Like all masons of that period, Norton would have been liable at very short notice to be taken off the job and transferred to do work for the King. To avoid disruption, some colleges made payments to the King to ensure that their men would not be pressed into his service..[24]The parishioners of St. Clement's would not have been able to pay the King, and so any work taking place on the church after 1351 might have been periodically interrupted.

7. Quarrying and Transporting the Stone

If we assume that someone like Richard Norton or one of his ancestors carved the head, we need to ask how the stone would have been quarried and then transported to the site and what tools he would have used.

The stone would probably have been dislodged from the quarry by means of a puggle (a flat spear-headed piece of steel on a long pole, which was the only method of quarrying used in Oxford until the late 19th century)..[25]Although this method seems laborious today, the use of a slower and more gentle means of extraction results in releasing the internal rock stress in a gentle way, resulting in fewer cracks and fissurers compared to the modern 'fast' methods.[26]

Once extracted from the quarry, the block of stone would have been transported to its destination by water or road, and because there was no straightforward water route from the Headington Quarry, the stone that was destined to become the head would have travelled by cart down the present Beaumont Road, Green Road, Old Road, and Cheney Lane to the bottom of Headington Hill, and then the short distance to the site of the church of St. Clement.

When the block of stone reached the church, the final work began. Marcus Cooper believes that the mason himself probably would have designed the head, and that the block of stone might have been roughly shaped at the quarry and then finished once it reached the church. .[27]

Our stonemason's tools would have been tried and tested for generations. Iron was introduced into the UK in the 6th century B.C., and the Romans perfected the heating and reheating of it in charcoal fires to produce 'tool steel', which was a special grade out of which all tools with cutting edges were made..[28]

The stonemason might have begun his work using a type of chisel called a 'pitcher', to round the edges of the rough block, but his most basic tools were various sizes of chisel, a wooden mallet, a punch (a small hammer-headed tool used in diagonal strokes to take off the surface stone of the block), and similar instruments.[29]Marcus Cooper was able to tell us that a pointed chisel would have been used to sculpt the finer details of the face and plaited hair on the head.[30]

All metal tools needed frequent sharpening: on larger work sites a toolmaker would have been in residence to sharpen and temper the tools, and although the whetstone was used for this purpose, fire-sharpening was considered the best method as it prolonged the life of the tool. Our stonemason might well have sharpened his own tools.

To fit the corbel and head into place, and if it was in a high position, our man would have needed scaffolding and some sort of hoisting gear. The main supports of large scaffolding in the Middle Ages were traditionally made of elm, and the platform on which the stonemason stood was wattlework, possibly made of hurdles from willows that grew in Stonesfield, north of Oxford. Materials for hoisting the block of stone into place would usually have consisted of a cradle or some kind of container, ropes and a pulley.[31]

9. The Significance and The Message

It is unlikely that we will ever know if the head represents a particular historical or religious figure, and the fact that it bears a tight wimple-like neck adornment further deepens the mystery, and one can only speculate as to whether it is male or female.[32]

If the head did come from St. Clement's Church, then it was viewed on a daily basis by one of the poorest and most needy populations of Oxford. The church was sited just on the outskirts of the city itself, separated by a river from the town, and populated mainly by people at the lower end of the economic scale: labourers, farmhands, servants, as well as some tradesmen and shopkeepers, and the local farmer.

The hardship and low economic status of this community is reflected in the type of burials in the church yard. In 2010 Oxford Archaeology carried out excavations on the Plain, on behalf of Jacobs Engineering, who were undertaking roadworks there. The results of the survey did not produce any evidence of medieval burials, but the dig covered only part of the old churchyard. The findings indicated that the majority of burials were of low status and that 'contaminated water supply, poor nutrition and living conditions associated with poverty would have impacted negatively on the general health of this population'. [33] There is no indication that the fortunes of the parishioners of St. Clements had declined since the Middle Ages, and it is therefore likely that this had always been a rather deprived area.

The people of St Clement's would have experienced much hardship on earth, and so it is not surprising that they should seek salvation and pin their hopes on a better life in the Hereafter: the church was seen as a vessel of salvation and every element of the physical building was a direct connection to the Divine. Religious doctrine permeated all aspects of life in the Middle ages and church attendance was obligatory.

As part of the fabric of the church, the corbel head would have taken its place amongst the other powerful imagery in the church. Carved corbels – often in the shape of animals or representing religious figures – were intended not only as a structural support for the physical building, but also as an aesthetic and moral support for the congregation. It would have been situated at the top of a column, or the base of an arch or eave, well above the heads of the congregation, so that one encountered it only when looking upwards towards the roof and, beyond that, towards Heaven. The head would appear to spring directly from God's house and would have sent a powerful message to the congregation.

It is difficult for the 21st century viewer to imagine the power that this corbel and the other art and objects displayed in the church would have had for the medieval worshipper. The door of the church represented the border between earthly trials and deprivations of the here and now on the outside, and the sanctity and promise of salvation within. Once inside, the parishioner would explore with awe and wonder the extensive decoration which covered the interior of the church, depicting in wood, glass, stone and paint scenes from the Bible, lives of Saints, and the real as well as metaphorical battles of the body and spirit. The extensive religious imagery carved into and emerging from the physical fabric of the church was designed to inspire and educate the lives of commoners and nobility alike, and as part of this potent iconography the stone corbel from St. Clements would have played its part in enriching the lives of those who encountered it.

Further Information

Arkell,W.J. Oxford Stone, Faber and Faber, London, 1947.

The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, The Statute of Laborers, 1351, Yale Law School/Lillian Goldman Law Library, retrieved 09/4/2014.

Alec Clifton-Taylor and A.S. Ireson, English Stone Building, Victor Gollancz in association with Peter Crawley, 1994.

Marcus Cooper, interview with the author, Ashmolean Museum, 24 April, 2014.

Gee, E.A., Oxford Masons 1370-1530, Royal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1953, reprinted from The Archaeological Journal, vol. 109, pp. 53-131.

Hislop, Malcolm, Medieval Masons, vol. 78, Shire Archaeology, 2009.

Stephanie Jenkins, Oxford History website: “Old Oxford: East Oxford: The Plain”.

Stephanie Jenkins, Headington website: “History:Miscellaneous:The Stone Quarries”.

J. Laird and M. Viggers, “A Late-Viking Burial at Magdalen Bridge, Oxford? . . . revisited”, (Available online at the Archaeology of East Oxford website)

Lobel (ed.), Victoria County History: A History of the County of Oxford, Vol. 5 (London: Oxford University Press, 1957), pp. 258-266.

Barry Magrill, “Figurated Corbels on Romanesque Churches: The Interface of Diverse Social Patterns Represented on Marginal Spaces”, Canadian Art Review/Review d'art Canadienne, XXXIV, Number 2 (2009), pp. 43-54.

Richard Marks, Image and Devotion in Late Medieval England (Sutton Publishing, 2004).

Oxford Archaeology, 'St Clement's Churchyard, The Plain, Oxford'. Archaeological Watching Brief Report, for Jacobs (Oxford Archaeology, October 2007.

Per Storemyr Archaeology and Conservation website: Experimental Archaeology: The traditional way of quarrying soapstone.

Portable Antiquities Scheme website. . http://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/71990

Veronica Sekules, Medieval Art, (Oxford University Press, 2001).

C.M. Woolgar, 'A Late Sixteenth-Century Map of St. Clement's, Oxford'. Oxoniensia, Vol. XLVI, (Oxford Architectural and Historical Society, 1981), pp. 94-98.

Find out more about:

July 2014