Highlights of the British Collection: East Oxford Archaeology

Object Biographies : An Anglo Saxon shield boss

from Magdalen Bridge, Oxford

by Jennifer Laird and Mark Viggers

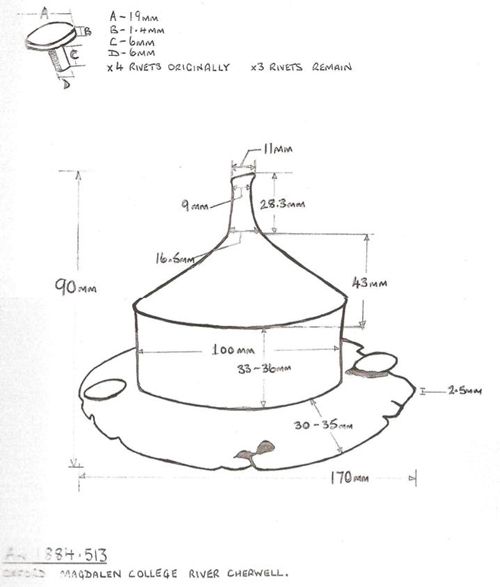

Shield boss AN1884.513, from the side

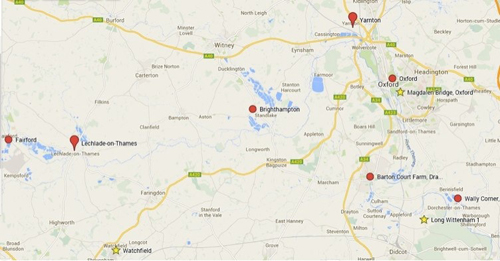

1. The Archaeology and location

In May 1884, dredging in the Cherwell uncovered an Anglo Saxon shield boss along with a spearhead. The location of these finds was under the bridge arch, furthest from Magdalen College, going east.

Both the shield boss and the spearhead are now held by the Ashmolean Museum. This object biography will concentrate on the shield boss due to the style, rarity and where it was found.

The Museum's record describes it as:

AN1884.513 Prof. H. N. Moseley, Linacre Professor of Physiology

A well preserved iron umbo or boss of an Anglo Saxon shield wanting only one of the flat circular headed rivets in the rim. The iron scarcely at all oxidised. The diameter 6 7/10”; diameter of the central, or raised portion, only 4 2/10”; diameter of the head of the rivets 15/20”. Projection of the boss from the shield: 4”. The apex ends in a flat round projection or button nearly 5/10” diameter. The sides of the raised portion are but slightly hollow, 1 4/10” hub and have a ridge at the angle or joining with the sloping top. It appears to have received a blow as if by a spear or an arrow.

The boss, found at Magdalen Bridge, Oxford during the dredging of the river Cherwell, under the eastern arch in 1884, is an uncommon and interesting artefact. It is a shame that it was not found in situ, in a cemetery with associated and datable grave goods. However, due to its more distinctive style, we can still attempt to tell its story using other boss of its type. Initially we identified the Magdalen boss as a Group 4 type, but then had to reassess this as we realised that the wider flange of the boss placed it into the group 5 category.

Shield boss AN1884.513, from the top

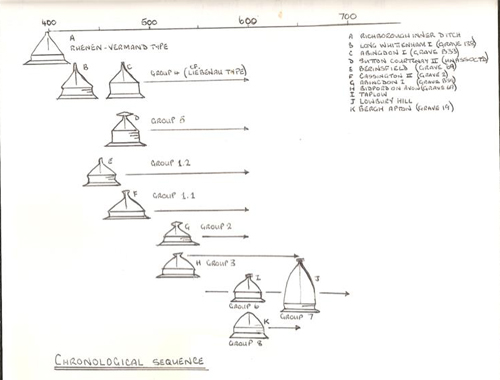

2. A brief history of the Germanic Migration Period shield bosses, groups 4 and 5

Group 4 bosses are a small group, with 14 bosses in the Upper Thames area. Group 5 is even smaller with 3 bosses in the Upper Thames area and only one other from Bidford on Avon.

Stylistically, group 5 bosses only differ from group 4 in that the flange and disc apex have a greater width. These differences are minor in comparison with other boss groups. We have decided to talk about both groups 4 and 5 as they have a common stylistic heritage and the grouping of these finds in a concentrated area is unusual.

The style of group 4 and 5 bosses can be traced back as far as the early Roman Iron Age (Jahn 1916, 173) in the area of and to the east of the River Elbe, East Germany. This Germanic boss style seems to disappear from cemeteries east of the Elbe in the later third and fourth centuries, but then reappear in cemeteries between the Elbe moving west to the Loire in France in the later fourth and fifth centuries.

Key

Key ![]() 5/6C Settlement

5/6C Settlement ![]() Group 5 boss & 5/6C settlement

Group 5 boss & 5/6C settlement ![]() Group 4 boss& 5/6C settlement

Group 4 boss& 5/6C settlement

Was this an indication of population migration?

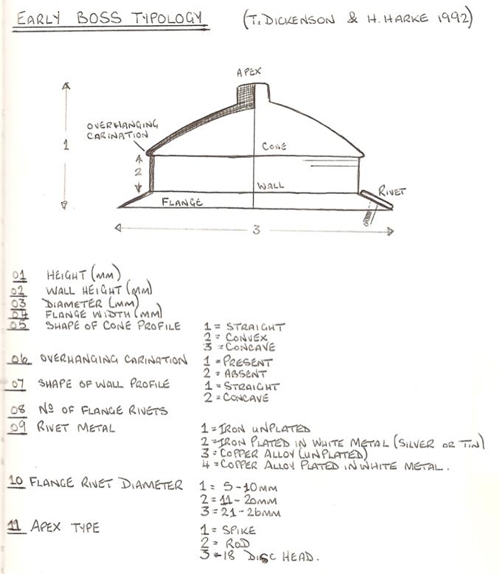

3. The physical aspects of the group 4 (and 5) boss

Group 4 (and 5) bosses are more distinctive in appearance than the other groups. Mostly, when we think of a shield boss, we think of a low domed profile, more in keeping with the later period Anglo Saxon and Viking style. This later style of boss was developed for a completely different style of combat. Battles were fought in a more massed formation i.e. a shield wall. The later shields were physically bigger and used in a more protective manner. Early/migration period shields were smaller and used more in an offensive manner, due to the fighting style being more individualistic, with more emphasis on the warrior’s skill, strength and bravery.

The bosses differ from the other groups in their height and narrowness, more so in their medium to high wall heights.

Boss height: 82 -119mm

Wall height: 20 - 35mm

Boss diameter: 125 - 156mm

Flange width: 15 - 21mm

The boss groups 4 and 5 are also distinctive in that they generally only have four boss rivets, and they have a spike or rod apex. In some cases, a disc is brazed onto the end of the rod. The Magdalen Boss does not have evidence of there ever being a disc attached.

Group 5 bosses differ only in the greater flange dimension (25 - 31mm), and, where fitted, the disc apexes are broader. (Dickinson and Harke, 1992).

A sheet of iron would be heated and beaten to form a cylinder shape that would form the wall. This cylinder would then have the bottom edge flared out to form the flange (to mount to the shield face with rivets). Another piece of iron would then be heated and beaten to form the upper cone shape. The two pieces are joined by forge welding around the circumference. Forge welding is where both parts to be joined would be heated to a high temperature, joined together, and then beaten so that the surfaces bond to form one piece of metal. The spike, or rod apex, is brazed into place inside the cone. If a disc is fitted, it would be brazed to the end of the rod.

We decided to have this particular shield boss, from Magdalen Bridge, recreated. You can see the result at the end of the paper. We chose a trusted and accomplished blacksmith friend of ours, Jason Green of Wieland Forge, to work with the original dimensions, along with numerous photographs and line drawings of the artefact itself. Although Jason has vast experience of making later period bosses, he remarked on how technically more difficult this style of boss was to make. After Jason had completed the boss to an incredibly high standard, he stated that, in his opinion, there would have been a specialist blacksmith producing this type of shield boss.

Bearing in mind the close proximity of other group 4 and 5 bosses found, could it be that there was a specialist blacksmith in this area? Or did the warriors from a specific area of Germany bring their shields and bosses with them during their migration?

5. Damage to the Anglo Saxon shield boss

On the cone of the boss itself, there seems to be an area that has suffered damage, as presented by Professor Moseley in his initial evaluation. Although we can only speculate from experience in re-enactment battles, we would guess that it was probably damage from a spear point. Most impact damage on a shield boss tends to be on the top (or upper) part of it, as in this case, due to blows being delivered in a downward motion. Also, on the flange, it seems that there are two holes of roughly the same diameter and shape in close proximity. One of the holes would have been for the, now missing, rivet, but there is some damage to the hole. Could it be that the second hole was made to secure the boss to the shield after the initial hole was damaged? Or might the second hole be down to deterioration? From our experience, and taking into account the expense and high regard the shield boss was held in, we consider the first explanation to be feasible.

“In the Germania, Tacitus mentions that the Germanic warrior’s worst disgrace was to lose

his shield in battle, but common sense suggests that for many men a hard-fought battle would have left them with little or no board, and all that would remain would be the metal boss. Nevertheless, re-fitting a new board to an existing boss would not be difficult and it may therefore be that the boss itself held the symbolic significance.”

(The English Warrior - from the earliest times to 1066. Stephen Pollington, Anglo Saxon Books 1996)

Cpmbat damage visible on the shiled boss

Oxford was founded in the late 9th century when Alfred the Great created a network of fortified towns called burghs across his kingdom. One of these was at Oxford. We have no archaeological evidence, so far, that there was a settlement in Oxford before this time. There may have been a village already existing there or King Alfred may have created a new town. The streets of late Anglo-Saxon Oxford were in a regular pattern suggesting a new town but we cannot be sure.

Oxford is first mentioned in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle in 911AD. It states: 'King Edward received the burghs of London and Oxford with all the lands belonging to them'.

Oxford soon became a flourishing town and fortress.

Could finding this Germanic style military equipment point to the ‘foederati’ or mercenary troops in the employ of post Roman Civitas administration centres, such as Dorchester on Thames? Potentially indicating a shift in sociopolitical structure rather than the ‘invasion’ of other areas of Britain.

Foederati and its usage and meaning was extended by the Roman practice of subsidising entire barbarian/Germanic tribes, in exchange for providing warriors to fight in the Roman armies. These tribes, in later years, became the Franks, Vandals, Alans and, best known, the Visigoths. At first, the Roman subsidy took the form of money or food, but as tax revenues dwindled in the 4th and 5th centuries, the foederati were billeted on local landowners, which came to be identical to being allowed to settle on Roman territory.

Dorchester on Thames is thought to have existed as a centre of Romano British administration into the 6th century, and as such, would have benefitted from the protection of the foederati. The Dorchester Belt is compelling evidence that there were foederati present there in the 5th century. This outstanding artefact is on display in the ‘England 400-1600’ gallery in the Ashmolean.

If we do take the idea of foederati presence as feasible, and there is compelling evidence, then how many groups of organised mercenaries were in Oxfordshire, and where could they have been?

Mark Viggers took on the challenge of creating an authentic Anglo Saxon shield to display this recreated boss, hopefully to show how it would have looked back in the 5/6C.

The link to Mark’s written report

The full Oxoniesia report by W. A. Seaby, can be found here: Late Dark Age Finds from the Cherwell and Ray 1876-1886 http://oxoniensia.org/volumes/1950/seaby.pdf This webpage also contains the report on the Viking stirrups, displayed in the Ashmolean Museum. We revisited the report on the Viking stirrups for ArchEoOx a couple of years ago.

The link to viking stirrups report

Although we know nothing about who owned or made this shield boss, we can use defined typology and previous finds to approximately date it using its style. As is the case with many object biographies, we have found ourselves asking more questions than gaining answers. We are hoping that the recreation of the boss and shield will give an idea of how an early Anglo Saxon shield would have looked.

We will, hopefully, go on to look, in more depth, at the very intriguing spearhead found with the shield boss in the future.

Further Information

Find out more about:

- Oxfordshire's Historic Archives

- British Collections Online - searchable database of the collection

July 2014